After having seen the basic elements of CP-SAT, this chapter will introduce you to the more complex constraints. These constraints are already focused on specific problems, such as routing or scheduling, but very generic and powerful within their domain. However, they also need more explanation on the correct usage.

- Tour Constraints:

add_circuit,add_multiple_circuit,add_reservoir_constraint_with_active - Intervals:

new_interval_var,new_interval_var_series,new_fixed_size_interval_var,new_optional_interval_var,new_optional_interval_var_series,new_optional_fixed_size_interval_var,new_optional_fixed_size_interval_var_series,add_no_overlap,add_no_overlap_2d,add_cumulative - Automaton Constraints:

add_automaton - Reservoir Constraints:

add_reservoir_constraint, - Piecewise Linear Constraints: Not officially part of CP-SAT, but we provide some free copy&pasted code to do it.

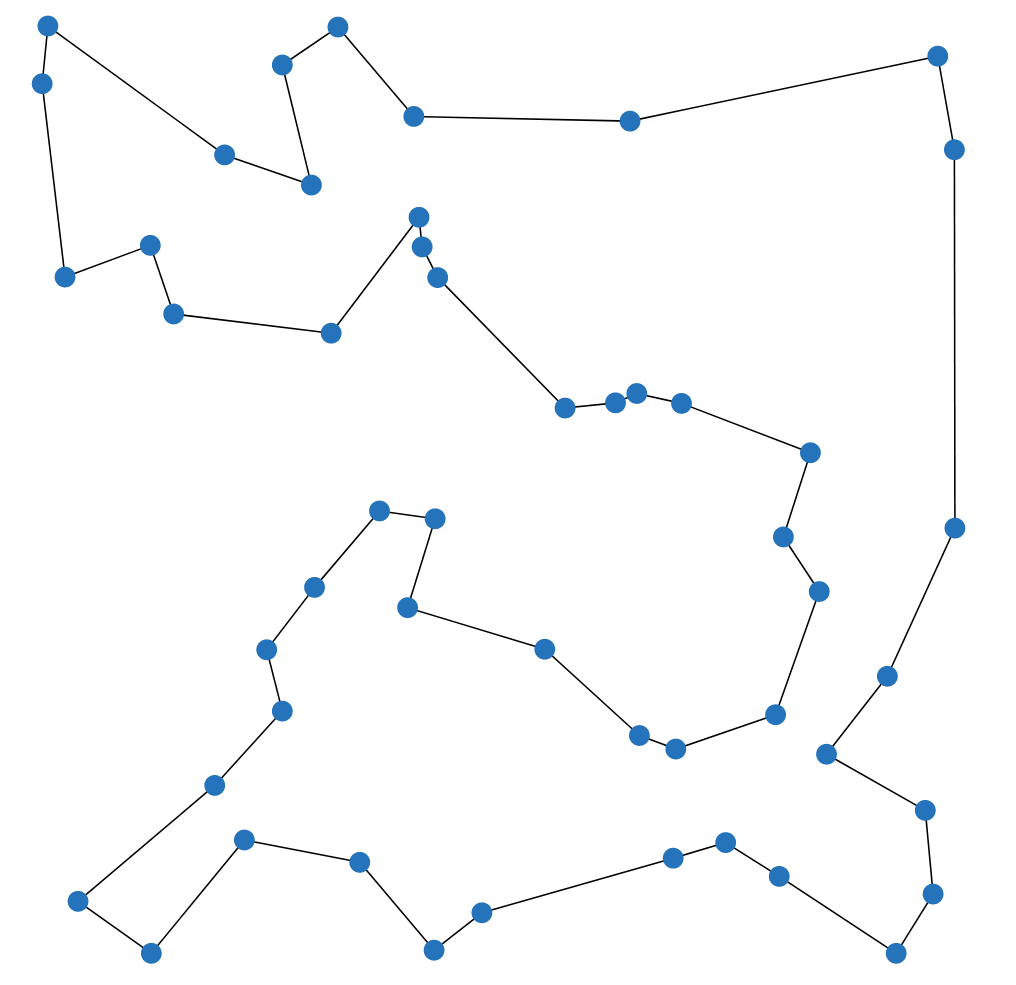

Routes and tours are essential in addressing optimization challenges across

various fields, far beyond traditional routing issues. For example, in DNA

sequencing, optimizing the sequence in which DNA fragments are assembled is

crucial, while in scientific research, methodically ordering the reconfiguration

of experiments can greatly reduce operational costs and downtime. The

add_circuit and add_multiple_circuit constraints in CP-SAT allow you to

easily model various scenarios. These constraints extend beyond the classical

Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP),

allowing for solutions where not every node needs to be visited and

accommodating scenarios that require multiple disjoint sub-tours. This

adaptability makes them invaluable for a broad spectrum of practical problems

where the sequence and arrangement of operations critically impact efficiency

and outcomes.

|

|---|

| The Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) asks for the shortest possible route that visits every vertex exactly once and returns to the starting vertex. |

The Traveling Salesman Problem is one of the most famous and well-studied combinatorial optimization problems. It is a classic example of a problem that is easy to understand, common in practice, but hard to solve. It also has a special place in the history of optimization, as many techniques that are now used generally were first developed for the TSP. If you have not done so yet, I recommend watching this talk by Bill Cook, or even reading the book In Pursuit of the Traveling Salesman.

Tip

If your problem is specifically the Traveling Salesperson Problem (TSP), you

might find the

Concorde solver

particularly effective. For problems closely related to the TSP, a Mixed

Integer Programming (MIP) solver may be more suitable, as many TSP variants

yield strong linear programming relaxations that MIP solvers can efficiently

exploit. Additionally, consider

OR-Tools Routing if

routing constitutes a significant aspect of your problem. However, for

scenarios where variants of the TSP are merely a component of a larger

problem, utilizing CP-SAT with the add_circuit or add_multiple_circuit

constraints can be very beneficial.

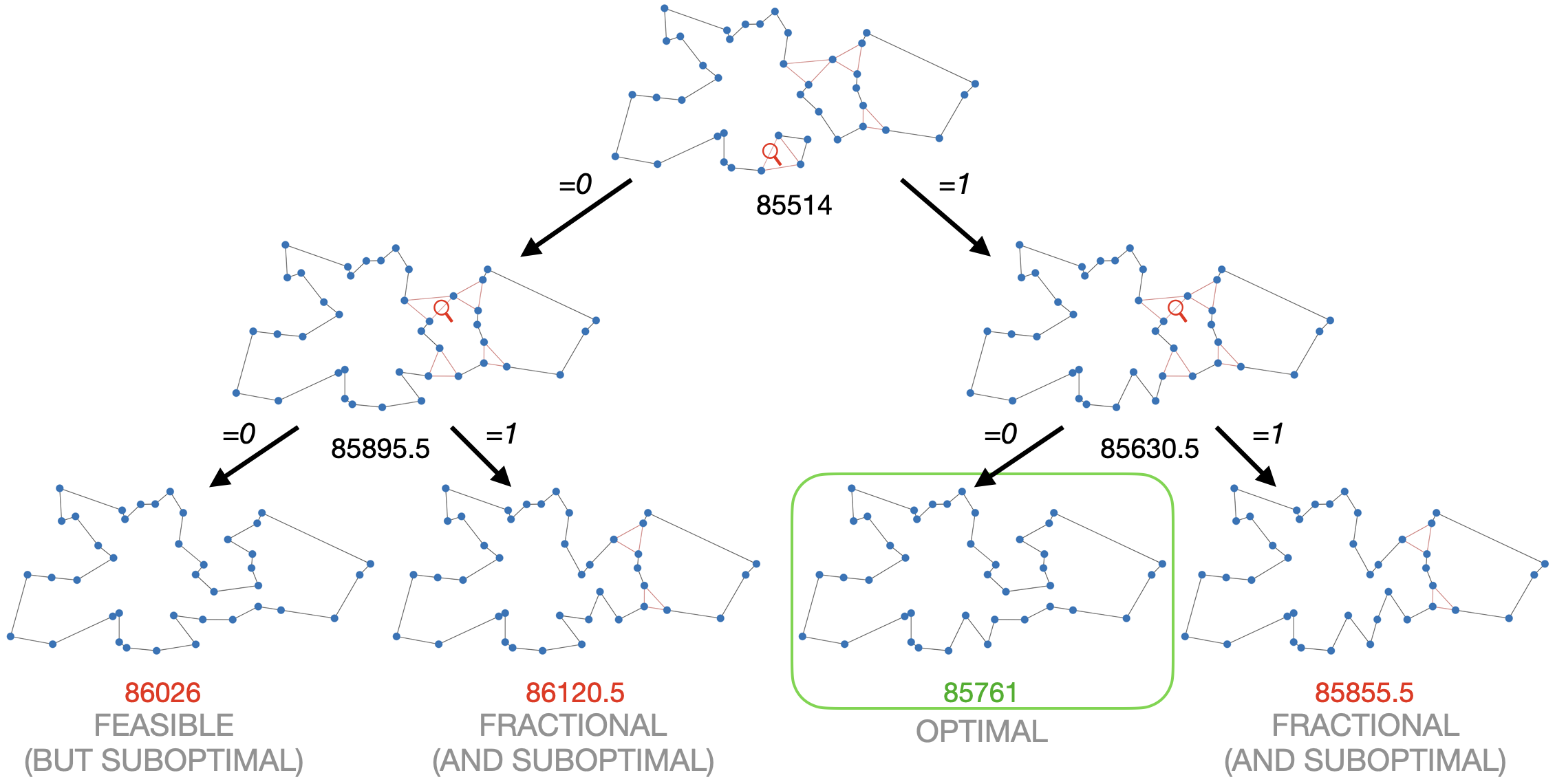

|

|---|

| This example shows why Mixed Integer Programming solvers are so good in solving the TSP. The linear relaxation (at the top) is already very close to the optimal solution. By branching, i.e., trying 0 and 1, on just two fractional variables, we not only find the optimal solution but can also prove optimality. The example was generated with the DIY TSP Solver. |

The add_circuit constraint is utilized to solve circuit problems within

directed graphs, even allowing loops. It operates by taking a list of triples

(u,v,var), where u and v denote the source and target vertices,

respectively, and var is a Boolean variable that indicates if an edge is

included in the solution. The constraint ensures that the edges marked as True

form a single circuit visiting each vertex exactly once, aside from vertices

with a loop set as True. Vertex indices should start at 0 and must not be

skipped to avoid isolation and infeasibility in the circuit.

Here is an example using the CP-SAT solver to address a directed Traveling Salesperson Problem (TSP):

from ortools.sat.python import cp_model

# Directed graph with weighted edges

dgraph = {(0, 1): 13, (1, 0): 17, ...(2, 3): 27}

# Initialize CP-SAT model

model = cp_model.CpModel()

# Boolean variables for each edge

edge_vars = {(u, v): model.new_bool_var(f"e_{u}_{v}") for (u, v) in dgraph.keys()}

# Circuit constraint for a single tour

model.add_circuit([(u, v, var) for (u, v), var in edge_vars.items()])

# Objective function to minimize total cost

model.minimize(sum(dgraph[(u, v)] * x for (u, v), x in edge_vars.items()))

# Solve model

solver = cp_model.CpSolver()

status = solver.solve(model)

if status in (cp_model.OPTIMAL, cp_model.FEASIBLE):

tour = [(u, v) for (u, v), x in edge_vars.items() if solver.value(x)]

print("Tour:", tour)

# Output: [(0, 1), (2, 0), (3, 2), (1, 3)], i.e., 0 -> 1 -> 3 -> 2 -> 0This constraint can be adapted for paths by adding a virtual enforced edge that

closes the path into a circuit, such as (3, 0, 1) for a path from vertex 0 to

vertex 3.

The add_circuit constraint can be creatively adapted to solve various related

problems. While there are more efficient algorithms for solving the Shortest

Path Problem, let us demonstrate how to adapt the add_circuit constraint for

educational purposes.

from ortools.sat.python import cp_model

# Define a weighted, directed graph with edge costs

dgraph = {(0, 1): 13, (1, 0): 17, ...(2, 3): 27}

source_vertex = 0

target_vertex = 3

# Add zero-cost loops for vertices not being the source or target

for v in [1, 2]:

dgraph[(v, v)] = 0

# Initialize CP-SAT model and variables

model = cp_model.CpModel()

edge_vars = {(u, v): model.new_bool_var(f"e_{u}_{v}") for (u, v) in dgraph}

# Define the circuit including a pseudo-edge from target to source

circuit = [(u, v, var) for (u, v), var in edge_vars.items()] + [

(target_vertex, source_vertex, 1)

]

model.add_circuit(circuit)

# Minimize total cost

model.minimize(sum(dgraph[(u, v)] * x for (u, v), x in edge_vars.items()))

# Solve and extract the path

solver = cp_model.CpSolver()

status = solver.solve(model)

if status in (cp_model.OPTIMAL, cp_model.FEASIBLE):

path = [(u, v) for (u, v), x in edge_vars.items() if solver.value(x) and u != v]

print("Path:", path)

# Output: [(0, 1), (1, 3)], i.e., 0 -> 1 -> 3This approach showcases the flexibility of the add_circuit constraint for

various tour and path problems. Explore further examples:

- Budget constrained tours: Optimize the largest possible tour within a specified budget.

-

Multiple tours:

Solve for

$k$ minimal tours covering all vertices.

You can model multiple disjoint tours using several add_circuit constraints,

as demonstrated in

this example.

If all tours share a common depot (vertex 0), the add_multiple_circuit

constraint is an alternative. However, this constraint does not allow you to

specify the number of tours, nor can it determine to which tour a particular

edge belongs. Therefore, the add_circuit constraint is often a superior

choice. Although the arguments for both constraints are identical, vertex 0

serves a unique role as the depot where all tours commence and conclude.

The table below displays the performance of the CP-SAT solver on various

instances of the TSPLIB, using the add_circuit constraint, under a 90-second

time limit. The performance can be considered reasonable, but can be easily

beaten by a Mixed Integer Programming solver.

| Instance | # vertices | runtime | lower bound | objective | opt. gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| att48 | 48 | 0.47 | 33522 | 33522 | 0 |

| eil51 | 51 | 0.69 | 426 | 426 | 0 |

| st70 | 70 | 0.8 | 675 | 675 | 0 |

| eil76 | 76 | 2.49 | 538 | 538 | 0 |

| pr76 | 76 | 54.36 | 108159 | 108159 | 0 |

| kroD100 | 100 | 9.72 | 21294 | 21294 | 0 |

| kroC100 | 100 | 5.57 | 20749 | 20749 | 0 |

| kroB100 | 100 | 6.2 | 22141 | 22141 | 0 |

| kroE100 | 100 | 9.06 | 22049 | 22068 | 0 |

| kroA100 | 100 | 8.41 | 21282 | 21282 | 0 |

| eil101 | 101 | 2.24 | 629 | 629 | 0 |

| lin105 | 105 | 1.37 | 14379 | 14379 | 0 |

| pr107 | 107 | 1.2 | 44303 | 44303 | 0 |

| pr124 | 124 | 33.8 | 59009 | 59030 | 0 |

| pr136 | 136 | 35.98 | 96767 | 96861 | 0 |

| pr144 | 144 | 21.27 | 58534 | 58571 | 0 |

| kroB150 | 150 | 58.44 | 26130 | 26130 | 0 |

| kroA150 | 150 | 90.94 | 26498 | 26977 | 2% |

| pr152 | 152 | 15.28 | 73682 | 73682 | 0 |

| kroA200 | 200 | 90.99 | 29209 | 29459 | 1% |

| kroB200 | 200 | 31.69 | 29437 | 29437 | 0 |

| pr226 | 226 | 74.61 | 80369 | 80369 | 0 |

| gil262 | 262 | 91.58 | 2365 | 2416 | 2% |

| pr264 | 264 | 92.03 | 49121 | 49512 | 1% |

| pr299 | 299 | 92.18 | 47709 | 49217 | 3% |

| linhp318 | 318 | 92.45 | 41915 | 52032 | 19% |

| lin318 | 318 | 92.43 | 41915 | 52025 | 19% |

| pr439 | 439 | 94.22 | 105610 | 163452 | 35% |

There are two prominent formulations to model the Traveling Salesman Problem

(TSP) without an add_circuit constraint: the

Dantzig-Fulkerson-Johnson (DFJ) formulation

and the

Miller-Tucker-Zemlin (MTZ) formulation.

The DFJ formulation is generally regarded as more efficient due to its stronger

linear relaxation. However, it requires lazy constraints, which are not

supported by the CP-SAT solver. When implemented without lazy constraints, the

performance of the DFJ formulation is comparable to that of the MTZ formulation

in CP-SAT. Nevertheless, both formulations perform significantly worse than the

add_circuit constraint. This indicates the superiority of using the

add_circuit constraint for handling tours and paths in such problems. Unlike

end users, the add_circuit constraint can utilize lazy constraints internally,

offering a substantial advantage in solving the TSP.

A special case of variables are the interval variables, that allow to model intervals, i.e., a span of some length with a start and an end. There are fixed length intervals, flexible length intervals, and optional intervals to model various use cases. These intervals become interesting in combination with the no-overlap constraints for 1D and 2D. We can use this for geometric packing problems, scheduling problems, and many other problems, where we have to prevent overlaps between intervals. These variables are special because they are actually not a variable, but a container that bounds separately defined start, length, and end variables.

There are four types of interval variables: new_interval_var,

new_fixed_size_interval_var, new_optional_interval_var, and

new_optional_fixed_size_interval_var. The new_optional_interval_var is the

most expressive but also the most expensive, while new_fixed_size_interval_var

is the least expressive and the easiest to optimize. All four types take a

start= variable. Intervals with fixed_size in their name require a constant

size= argument defining the interval length. Otherwise, the size= argument

can be a variable in combination with an end= variable, which complicates the

solution. Intervals with optional in their name include an is_present=

argument, a boolean indicating if the interval is present. The no-overlap

constraints, discussed later, apply only to intervals that are present, allowing

for modeling problems with multiple resources or optional tasks. Instead of a

pure integer variable, all arguments also accept an affine expression, e.g.,

start=5*start_var+3.

model = cp_model.CpModel()

start_var = model.new_int_var(0, 100, "start")

length_var = model.new_int_var(10, 20, "length")

end_var = model.new_int_var(0, 100, "end")

is_present_var = model.new_bool_var("is_present")

# creating an interval whose length can be influenced by a variable (more expensive)

flexible_interval = model.new_interval_var(

start=start_var, size=length_var, end=end_var, name="flexible_interval"

)

# creating an interval of fixed length

fixed_interval = model.new_fixed_size_interval_var(

start=start_var,

size=10, # needs to be a constant

name="fixed_interval",

)

# creating an interval that can be present or not and whose length can be influenced by a variable (most expensive)

optional_interval = model.new_optional_interval_var(

start=start_var,

size=length_var,

end=end_var,

is_present=is_present_var,

name="optional_interval",

)

# creating an interval that can be present or not

optional_fixed_interval = model.new_optional_fixed_size_interval_var(

start=start_var,

size=10, # needs to be a constant

is_present=is_present_var,

name="optional_fixed_interval",

)These interval variables are not useful on their own, as we could have easily achieved the same with a simple linear constraint. However, CP-SAT provides special constraints for these interval variables, that would actually be much harder to model by hand and are also much more efficient.

CP-SAT offers the following three constraints for intervals:

add_no_overlap,add_no_overlap_2d, add_cumulative. add_no_overlap is used

to prevent overlaps between intervals on a single dimension, e.g., time.

add_no_overlap_2d is used to prevent overlaps between intervals on two

dimensions, e.g., for packing rectangles. add_cumulative is used to model a

resource constraint, where the sum of the demands of the overlapping intervals

must not exceed the capacity of the resource.

The add_no_overlap constraints takes a list of (optional) interval variables

and ensures that no two present intervals overlap.

model.add_no_overlap(

interval_vars=[

flexible_interval,

fixed_interval,

optional_interval,

optional_fixed_interval,

# ...

]

)The add_no_overlap_2d constraints takes two lists of (optional) interval and

ensures that for every i and j either x_intervals[i] and x_intervals[j]

or y_intervals[i] and y_intervals[j] do not overlap. Thus, both lists must

have the same length as x_intervals[i] and y_intervals[i] are considered

belonging together. If either x_intervals[i] or y_intervals[i] are optional,

the whole object is optional.

model.add_no_overlap_2d(

x_intervals=[

flexible_interval,

fixed_interval,

optional_interval,

optional_fixed_interval,

# ...

],

y_intervals=[

flexible_interval,

fixed_interval,

optional_interval,

optional_fixed_interval,

# ...

],

)The add_cumulative constraint is used to model a resource constraint, where

the sum of the demands of the overlapping intervals must not exceed the capacity

of the resource. An example could be scheduling the usage of certain energy

intensive machines, where the sum of the energy demands must not exceed the

capacity of the power grid. It takes a list of intervals, a list of demands, and

a capacity variable. The list of demands must have the same length as the list

of intervals, as the demands of the intervals are matched by index. As capacity

and demands can be variables (or affine expressions), quite complex resource

constraints can be modeled.

demand_vars = [model.new_int_var(1, 10, f"demand_{i}") for i in range(4)]

capacity_var = model.new_int_var(1, 100, "capacity")

model.add_cumulative(

intervals=[

flexible_interval,

fixed_interval,

optional_interval,

optional_fixed_interval,

],

demands=demand_vars,

capacity=capacity_var,

)Warning

Do not directly jump to intervals when you have a scheduling problem. Intervals are great if you actually have a somewhat continuous time or space that you need to schedule. If you have a more discrete problem, such as a scheduling problem with a fixed number of slots, you can often model this problem much more efficiently using simple Boolean variables and constraints. Especially if you can use domain knowledge to find clusters of meetings that cannot overlap, this can be much more efficient.

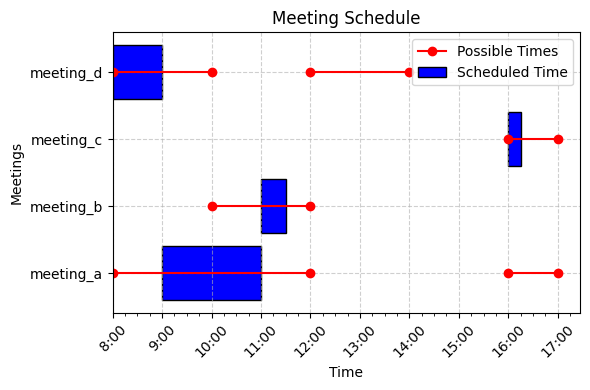

Let us examine a few examples of how to use these constraints effectively.

Assume we have a conference room and need to schedule several meetings. Each

meeting has a fixed length and a range of possible start times. The time slots

are in 5-minute intervals starting at 8:00 AM and ending at 6:00 PM. Thus, there

are new_fixed_size_interval_var to model the intervals. The add_no_overlap

constraint ensures no two meetings overlap, and domains for the start time can

model the range of possible start times.

To handle input data, let us define a namedtuple to store the meeting and two

functions to convert between time and index.

# Convert time to index and back

def t_to_idx(hour, minute):

return (hour - 8) * 12 + minute // 5

def idx_to_t(time_idx):

hour = 8 + time_idx // 12

minute = (time_idx % 12) * 5

return f"{hour}:{minute:02d}"

# Define meeting information using namedtuples

MeetingInfo = namedtuple("MeetingInfo", ["start_times", "duration"])Then let us create a few meetings we want to schedule.

# Meeting definitions

meetings = {

"meeting_a": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[

[t_to_idx(8, 0), t_to_idx(12, 0)],

[t_to_idx(16, 0), t_to_idx(17, 0)],

],

duration=120 // 5, # 2 hours

),

"meeting_b": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[

[t_to_idx(10, 0), t_to_idx(12, 0)],

],

duration=30 // 5, # 30 minutes

),

"meeting_c": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[

[t_to_idx(16, 0), t_to_idx(17, 0)],

],

duration=15 // 5, # 15 minutes

),

"meeting_d": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[

[t_to_idx(8, 0), t_to_idx(10, 0)],

[t_to_idx(12, 0), t_to_idx(14, 0)],

],

duration=60 // 5, # 1 hour

),

}Now we can create the CP-SAT model and add the intervals and constraints.

# Create a new CP-SAT model

model = cp_model.CpModel()

# Create start time variables for each meeting

start_time_vars = {

meeting_name: model.new_int_var_from_domain(

cp_model.Domain.from_intervals(meeting_info.start_times),

f"start_{meeting_name}",

)

for meeting_name, meeting_info in meetings.items()

}

# Create interval variables for each meeting

interval_vars = {

meeting_name: model.new_fixed_size_interval_var(

start=start_time_vars[meeting_name],

size=meeting_info.duration,

name=f"interval_{meeting_name}",

)

for meeting_name, meeting_info in meetings.items()

}

# Ensure that now two meetings overlap

model.add_no_overlap(list(interval_vars.values()))And finally, we can solve the model and extract the solution.

# Solve the model

solver = cp_model.CpSolver()

status = solver.solve(model)

# Extract and print the solution

scheduled_times = {}

if status in (cp_model.OPTIMAL, cp_model.FEASIBLE):

for meeting_name in meetings:

start_time = solver.value(start_time_vars[meeting_name])

scheduled_times[meeting_name] = start_time

print(f"{meeting_name} starts at {idx_to_t(start_time)}")

else:

print("No feasible solution found.")Doing some quick magic with matplotlib, we can visualize the schedule.

|

|---|

| A possible non-overlapping schedule for the above example. The instance is quite simple, but you could try adding some more meetings. |

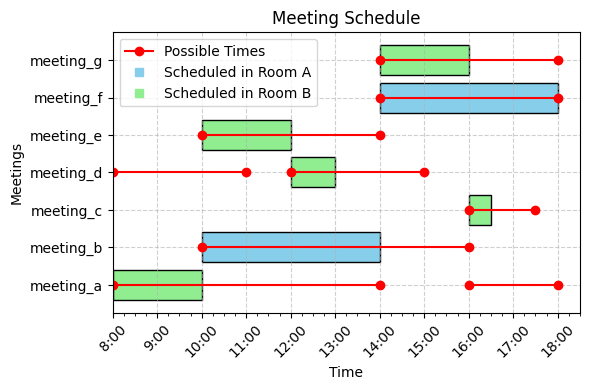

Now, imagine we have multiple resources, such as multiple conference rooms, and

we need to schedule the meetings such that no two meetings overlap in the same

room. This can be modeled with optional intervals, where the intervals exist

only if the meeting is scheduled in the room. The add_no_overlap constraint

ensures that no two meetings overlap in the same room.

Because we now have two rooms, we need to create a more challenging instance first. Otherwise, the solver may not need to use both rooms. We do this by simply adding more and longer meetings.

# Meeting definitions

meetings = {

"meeting_a": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[

[t_to_idx(8, 0), t_to_idx(12, 0)],

[t_to_idx(16, 0), t_to_idx(16, 0)],

],

duration=120 // 5,

),

"meeting_b": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[[t_to_idx(10, 0), t_to_idx(12, 0)]], duration=240 // 5

),

"meeting_c": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[[t_to_idx(16, 0), t_to_idx(17, 0)]], duration=30 // 5

),

"meeting_d": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[

[t_to_idx(8, 0), t_to_idx(10, 0)],

[t_to_idx(12, 0), t_to_idx(14, 0)],

],

duration=60 // 5,

),

"meeting_e": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[[t_to_idx(10, 0), t_to_idx(12, 0)]], duration=120 // 5

),

"meeting_f": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[[t_to_idx(14, 0), t_to_idx(14, 0)]], duration=240 // 5

),

"meeting_g": MeetingInfo(

start_times=[[t_to_idx(14, 0), t_to_idx(16, 0)]], duration=120 // 5

),

}This time, we need to create an interval variable for each room and meeting, as well as a Boolean variable indicating if the meeting is scheduled in the room. We cannot use the same interval variable for multiple rooms, as otherwise the interval would be present in both rooms.

# Create the model

model = cp_model.CpModel()

# Create start time and room variables

start_time_vars = {

name: model.new_int_var_from_domain(

cp_model.Domain.from_intervals(info.start_times), f"start_{name}"

)

for name, info in meetings.items()

}

rooms = ["room_a", "room_b"]

room_vars = {

name: {room: model.new_bool_var(f"{name}_in_{room}") for room in rooms}

for name in meetings

}

# Create interval variables and add no-overlap constraint

interval_vars = {

name: {

# We need a separate interval for each room

room: model.new_optional_fixed_size_interval_var(

start=start_time_vars[name],

size=info.duration,

is_present=room_vars[name][room],

name=f"interval_{name}_in_{room}",

)

for room in rooms

}

for name, info in meetings.items()

}Now we can enforce that each meeting is assigned to exactly one room and that there is no overlap between meetings in the same room.

# Ensure each meeting is assigned to exactly one room

for name, room_dict in room_vars.items():

model.add_exactly_one(room_dict.values())

for room in rooms:

model.add_no_overlap([interval_vars[name][room] for name in meetings])Again, doing some quick magic with matplotlib, we get the following schedule.

|

|---|

| A possible non-overlapping schedule for the above example with multiple rooms. |

Tip

You could easily extend this model to schedule as many meetings as possible using an objective function. You could also maximize the distance between two meetings by using a variable size interval. This would be a good exercise to try.

Let us examine how to check if a set of rectangles can be packed into a container without overlaps. This is a common problem in logistics, where boxes must be packed into a container, or in cutting stock problems, where pieces are cut from a larger material.

First, we define namedtuples for the rectangles and the container.

from collections import namedtuple

# Define namedtuples for rectangles and container

Rectangle = namedtuple("Rectangle", ["width", "height"])

Container = namedtuple("Container", ["width", "height"])

# Example usage

rectangles = [Rectangle(width=2, height=3), Rectangle(width=4, height=5)]

container = Container(width=10, height=10)Next, we create variables for the bottom-left corners of the rectangles. These variables are constrained to ensure the rectangles remain within the container.

model = cp_model.CpModel()

# Create variables for the bottom-left corners of the rectangles

x_vars = [

model.new_int_var(0, container.width - box.width, name=f"x1_{i}")

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

y_vars = [

model.new_int_var(0, container.height - box.height, name=f"y1_{i}")

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]Next, we create interval variables for each rectangle. The start of these

intervals corresponds to the bottom-left corner, and the size is the width or

height of the rectangle. We use the add_no_overlap_2d constraint to ensure

that no two rectangles overlap.

# Create interval variables representing the width and height of the rectangles

x_interval_vars = [

model.new_fixed_size_interval_var(

start=x_vars[i], size=box.width, name=f"x_interval_{i}"

)

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

y_interval_vars = [

model.new_fixed_size_interval_var(

start=y_vars[i], size=box.height, name=f"y_interval_{i}"

)

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

# Ensure no two rectangles overlap

model.add_no_overlap_2d(x_interval_vars, y_interval_vars)The optional intervals with flexible length allow us to model rotations and find the largest possible packing. The code may appear complex, but it remains straightforward considering the problem's complexity.

First, we define namedtuples for the rectangles and the container.

from collections import namedtuple

from ortools.sat.python import cp_model

# Define namedtuples for rectangles and container

Rectangle = namedtuple("Rectangle", ["width", "height", "value"])

Container = namedtuple("Container", ["width", "height"])

# Example usage

rectangles = [

Rectangle(width=2, height=3, value=1),

Rectangle(width=4, height=5, value=1),

]

container = Container(width=10, height=10)Next, we create variables for the coordinates of the rectangles. This includes variables for the bottom-left and top-right corners, as well as a boolean variable to indicate if a rectangle is rotated.

model = cp_model.CpModel()

# Create variables for the bottom-left and top-right corners of the rectangles

bottom_left_x_vars = [

model.new_int_var(0, container.width, name=f"x1_{i}")

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

bottom_left_y_vars = [

model.new_int_var(0, container.height, name=f"y1_{i}")

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

upper_right_x_vars = [

model.new_int_var(0, container.width, name=f"x2_{i}")

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

upper_right_y_vars = [

model.new_int_var(0, container.height, name=f"y2_{i}")

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

# Create variables to indicate if a rectangle is rotated

rotated_vars = [model.new_bool_var(f"rotated_{i}") for i in range(len(rectangles))]We then create variables for the width and height of each rectangle, adjusting for rotation. Constraints ensure these variables are set correctly based on whether the rectangle is rotated.

# Create variables for the width and height, adjusted for rotation

width_vars = []

height_vars = []

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles):

domain = cp_model.Domain.from_values([box.width, box.height])

width_vars.append(model.new_int_var_from_domain(domain, name=f"width_{i}"))

height_vars.append(model.new_int_var_from_domain(domain, name=f"height_{i}"))

# There are two possible assignments for width and height

model.add_allowed_assignments(

[width_vars[i], height_vars[i], rotated_vars[i]],

[(box.width, box.height, 0), (box.height, box.width, 1)],

)Next, we create a boolean variable indicating if a rectangle is packed or not, and then interval variables representing its occupied space in the container. These intervals are used to enforce the no-overlap constraint.

# Create variables indicating if a rectangle is packed

packed_vars = [model.new_bool_var(f"packed_{i}") for i in range(len(rectangles))]

# Create interval variables representing the width and height of the rectangles

x_interval_vars = [

model.new_optional_interval_var(

start=bottom_left_x_vars[i],

size=width_vars[i],

is_present=packed_vars[i],

end=upper_right_x_vars[i],

name=f"x_interval_{i}",

)

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

y_interval_vars = [

model.new_optional_interval_var(

start=bottom_left_y_vars[i],

size=height_vars[i],

is_present=packed_vars[i],

end=upper_right_y_vars[i],

name=f"y_interval_{i}",

)

for i, box in enumerate(rectangles)

]

# Ensure no two rectangles overlap

model.add_no_overlap_2d(x_interval_vars, y_interval_vars)Finally, we maximize the number of packed rectangles by defining an objective function.

# Maximize the number of packed rectangles

model.maximize(sum(box.value * x for x, box in zip(packed_vars, rectangles))) |

|---|

| This dense packing was found by CP-SAT in less than 0.3s, which is quite impressive and seems to be more efficient than a naive Gurobi implementation. |

You can find the full code here:

| Problem Variant | Code |

|---|---|

| Deciding feasibility of packing rectangles without rotations | ./evaluations/packing/solver/packing_wo_rotations.py |

| Finding the largest possible packing of rectangles without rotations | ./evaluations/packing/solver/knapsack_wo_rotations.py |

| Deciding feasibility of packing rectangles with rotations | ./evaluations/packing/solver/packing_with_rotations.py |

| Finding the largest possible packing of rectangles with rotations | ./evaluations/packing/solver/knapsack_with_rotations.py |

CP-SAT is good at finding a feasible packing, but incapable of proving infeasibility in most cases. When using the knapsack variant, it can still pack most of the rectangles even for the larger instances.

In earlier versions of CP-SAT, the performance of no-overlap constraints was greatly influenced by the resolution. This impact has evolved, yet it remains somewhat inconsistent. In a notebook example, I explored how resolution affects the execution time of the no-overlap constraint in versions 9.3 and 9.8 of CP-SAT. For version 9.3, there is a noticeable increase in execution time as the resolution grows. Conversely, in version 9.8, execution time actually reduces when the resolution is higher, a finding supported by repeated tests. This unexpected behavior suggests that the performance of CP-SAT regarding no-overlap constraints has not stabilized and may continue to vary in upcoming versions.

| Resolution | Runtime (CP-SAT 9.3) | Runtime (CP-SAT 9.8) |

|---|---|---|

| 1x | 0.02s | 0.03s |

| 10x | 0.7s | 0.02s |

| 100x | 7.6s | 1.1s |

| 1000x | 75s | 40.3s |

| 10_000x | >15min | 0.4s |

This notebook was used to create the table above.

However, while playing around with less documented features, I noticed that the performance for the older version can be improved drastically with the following parameters:

solver.parameters.use_energetic_reasoning_in_no_overlap_2d = True

solver.parameters.use_timetabling_in_no_overlap_2d = True

solver.parameters.use_pairwise_reasoning_in_no_overlap_2d = TrueWith the latest version of CP-SAT, I did not notice a significant difference in performance when using these parameters.

Automaton constraints model finite state machines, enabling the representation of feasible transitions between states. This is particularly useful in software verification, where it is essential to ensure that a program follows a specified sequence of states. Given the critical importance of verification in research, there is likely a dedicated audience that appreciates this constraint. However, others may prefer to proceed to the next section.

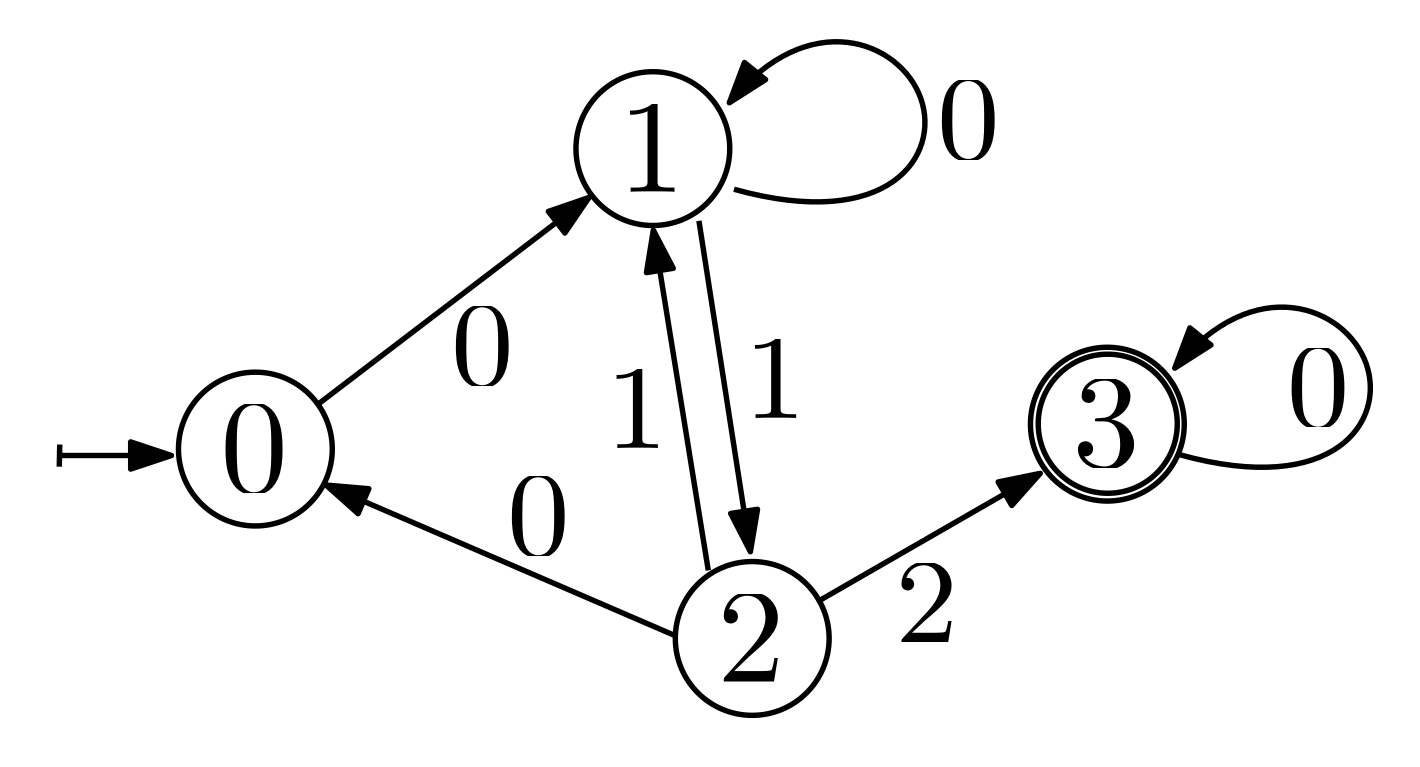

|

|---|

| An example of a finite state machine with four states and seven transitions. State 0 is the initial state, and state 3 is the final state. |

The automaton operates as follows: We have a list of integer variables

transition_variables that represent the transition values. Starting from the

starting_state, the next state is determined by the transition triple

(state, transition_value, next_state) matching the first transition variable.

If no such triple is found, the model is infeasible. This process repeats for

each subsequent transition variable. It is crucial that the final transition

leads to a final state (possibly via a loop); otherwise, the model remains

infeasible.

The state machine from the example can be modeled as follows:

model = cp_model.CpModel()

transition_variables = [model.new_int_var(0, 2, f"transition_{i}") for i in range(4)]

transition_triples = [

(0, 0, 1), # If in state 0 and the transition value is 0, go to state 1

(1, 0, 1), # If in state 1 and the transition value is 0, stay in state 1

(1, 1, 2), # If in state 1 and the transition value is 1, go to state 2

(2, 0, 0), # If in state 2 and the transition value is 0, go to state 0

(2, 1, 1), # If in state 2 and the transition value is 1, go to state 1

(2, 2, 3), # If in state 2 and the transition value is 2, go to state 3

(3, 0, 3), # If in state 3 and the transition value is 0, stay in state 3

]

model.add_automaton(

transition_variables=transition_variables,

starting_state=0,

final_states=[3],

transition_triples=transition_triples,

)The assignment [0, 1, 2, 0] would be a feasible solution for this model,

whereas the assignment [1, 0, 1, 2] would be infeasible because state 0 has no

transition for value 1. Similarly, the assignment [0, 0, 1, 1] would be

infeasible as it does not end in a final state.

Sometimes, we need to keep the balance between inflows and outflows of a

reservoir. The name giving example is a water reservoir, where we need to keep

the water level between a minimum and a maximum level. The reservoir constraint

takes a list of time variables, a list of integer level changes, and the minimum

and maximum level of the reservoir. If the affine expression times[i] is

assigned a value t, then the current level changes by level_changes[i]. Note

that at the moment, variable level changes are not supported, which means level

changes are constant at time t. The constraint ensures that the level stays

between the minimum and maximum level at all time, i.e.

sum(level_changes[i] if times[i] <= t) in [min_level, max_level].

There are many other examples apart from water reservoirs, where you need to

balance demands and supplies, such as maintaining a certain stock level in a

warehouse, or ensuring a certain staffing level in a clinic. The

add_reservoir_constraint constraint in CP-SAT allows you to model such

problems easily.

In the following example, times[i] represents the time at which the change

level_changes[i] will be applied, thus both lists needs to be of the same

length. The reservoir level starts at 0, and the minimum level has to be

times = [model.new_int_var(0, 10, f"time_{i}") for i in range(10)]

level_changes = [1] * 10

model.add_reservoir_constraint(

times=times,

level_changes=level_changes,

min_level=-10,

max_level=10,

)Additionally, the add_reservoir_constraint_with_active constraint allows you

to model a reservoir with optional changes. Here, we additionally have a list

of Boolean variables actives, where actives[i] indicates if the change

level_changes[i] takes place, i.e. if

sum(level_changes[i] * actives[i] if times[i] <= t) in [min_level, max_level]

If a change is not active, it is as if it does not exist, and the reservoir

level remains the same, independent of the time and change values.

times = [model.new_int_var(0, 10, f"time_{i}") for i in range(10)]

level_changes = [1] * 10

actives = [model.new_bool_var(f"active_{i}") for i in range(10)]

model.add_reservoir_constraint_with_active(

times=times,

level_changes=level_changes,

actives=actives,

min_level=-10,

max_level=10,

)To illustrate the usage of the reservoir constraint, we look at an example for scheduling nurses in a clinic. For the full example, take a look at the notebook.

The clinic needs to ensure that there are always enough nurses available without over-staffing too much. For a 12-hour work day, we model the demands for nurses as integers for each hour of the day.

# a positive number means we need more nurses, a negative number means we need fewer nurses.

demand_change_at_t = [3, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, -1, 0, -1, 0, -3]

demand_change_times = list(range(len(demand_change_at_t))) # [0, 1, ..., 12]We have a list of nurses, each with an individual availability as well as a maximum shift length.

max_shift_length = 5

# begin and end of the availability of each nurse

nurse_availabilities = 2 * [

(0, 7),

(0, 4),

(0, 8),

(2, 9),

(1, 5),

(5, 12),

(7, 12),

(0, 12),

(4, 12),

]We now initialize all relevant variables of the model. Each nurse is assigned a start and end time of their shift as well as a Boolean variable indicating if they are working at all.

# boolean variable to indicate if a nurse is scheduled

nurse_scheduled = [

model.new_bool_var(f"nurse_{i}_scheduled") for i in range(len(nurse_availabilities))

]

# model the begin and end of each shift

shifts_begin = [

model.new_int_var(begin, end, f"begin_nurse_{i}")

for i, (begin, end) in enumerate(nurse_availabilities)

]

shifts_end = [

model.new_int_var(begin, end, f"end_nurse_{i}")

for i, (begin, end) in enumerate(nurse_availabilities)

]We now add some basic constraints to ensure that the shifts are valid.

for begin, end in zip(shifts_begin, shifts_end):

model.add(end >= begin) # make sure the end is after the begin

model.add(end - begin <= max_shift_length) # make sure, the shifts are not too longOur reservoir level is the number of nurses scheduled at any time minus the demand for nurses up until that point. We can now add the reservoir constraint to ensure that we have enough nurses available at all times while not having too many nurses scheduled (i.e., the reservoir level is between 0 and 2). We have three types of changes in the reservoir:

- The demand for nurses changes at the beginning of each hour. For these we use fixed integer times and activate all changes. Note that the demand changes are negated, as an increase in demand lowers the reservoir level.

- If a nurse begins a shift, we increase the reservoir level by 1. We use the

shifts_beginvariables as times and change the reservoir level only if the nurse is scheduled. - Once a nurse ends a shift, we decrease the reservoir level by 1. We use the

shifts_endvariables as times and change the reservoir level only if the nurse is scheduled.

times = demand_change_times

demands = [

-demand for demand in demand_change_at_t

] # an increase in demand lowers the reservoir

actives = [1] * len(demand_change_times)

times += list(shifts_begin)

demands += [1] * len(shifts_begin) # a nurse begins a shift

actives += list(nurse_scheduled)

times += list(shifts_end)

demands += [-1] * len(shifts_end) # a nurse ends a shift

actives += list(nurse_scheduled)

model.add_reservoir_constraint_with_active(

times=times,

level_changes=demands,

min_level=0,

max_level=2,

actives=actives,

)Note

The reservoir constraints can express conditions that are difficult to model "by hand". However, while I do not have much experience with them, I would not expect them to be particularly easy to optimize. Let me know if you have either good or bad experiences with them in practice and for which problem scales they work well.

In practice, you often have cost functions that are not linear. For example, consider a production problem where you have three different items you produce. Each item has different components, you have to buy. The cost of the components will first decrease with the amount you buy, then at some point increase again as your supplier will be out of stock and you have to buy from a more expensive supplier. Additionally, you only have a certain amount of customers willing to pay a certain price for your product. If you want to sell more, you will have to lower the price, which will decrease your profit.

Let us assume such a function looks like

Using linear constraints (model.add) and reification (.only_enforce_if), we

can model such a piecewise linear function in CP-SAT. For this we simply use

boolean variables to decide for a segment, and then activate the corresponding

linear constraint via reification. However, this has two problems in CP-SAT, as

shown in the next figure.

-

Problem A: Even if we can express a segment as a linear function, the result of the function may not be integral. In the example,

$f(5)$ would be$3.5$ and, thus, if we enforce$y=f(x)$ ,$x$ would be prohibited to be$5$ , which is not what we want. There are two options now. Either, we use a more complex piecewise linear approximation that ensures that the function will always yield integral solutions or we use inequalities instead. The first solution has the issue that this can require too many segments, making it far too expensive to optimize. The second solution will be a weaker constraint as now we can only enforce$y<=f(x)$ or$y>=f(x)$ , but not$y=f(x)$ . If you try to enforce it by$y<=f(x)$ and$y>=f(x)$ , you will end with the same infeasibility as before. However, often an inequality will be enough. If the problem is to prevent$y$ from becoming too large, you use$y<=f(x)$ , if the problem is to prevent$y$ from becoming too small, you use$y>=f(x)$ . If we want to represent the costs by$f(x)$ , we would use$y>=f(x)$ to minimize the costs. -

Problem B: The canonical representation of a linear function is

$y=ax+b$ . However, this will often require non-integral coefficients. Luckily, we can automatically scale them up to integral values by adding a scaling factor. The inequality$y=0.5x+0.5$ in the example can also be represented as$2y=x+1$ . I will spare you the math, but it just requires a simple trick with the least common multiple. Of course, the required scaling factor can become large, and at some point lead to overflows.

An implementation could now look as follows:

# We want to enforce y=f(x)

x = model.new_int_var(0, 7, "x")

y = model.new_int_var(0, 5, "y")

# use boolean variables to decide for a segment

segment_active = [model.new_bool_var("segment_1"), model.new_bool_var("segment_2")]

model.add_at_most_one(segment_active) # enforce one segment to be active

# Segment 1

# if 0<=x<=3, then y >= 0.5*x + 0.5

model.add(2 * y >= x + 1).only_enforce_if(segment_active[0])

model.add(x >= 0).only_enforce_if(segment_active[0])

model.add(x <= 3).only_enforce_if(segment_active[0])

# Segment 2

model.add(_SLIGHTLY_MORE_COMPLEX_INEQUALITY_).only_enforce_if(segment_active[1])

model.add(x >= 3).only_enforce_if(segment_active[1])

model.add(x <= 7).only_enforce_if(segment_active[1])

model.minimize(y)

# if we were to maximize y, we would have used <= instead of >=This can be quite tedious, but luckily, I wrote a small helper class that will do this automatically for you. You can find it in ./utils/piecewise_functions. Simply copy it into your code.

This code does some further optimizations:

- Considering every segment as a separate case can be quite expensive and inefficient. Thus, it can make a serious difference if you can combine multiple segments into a single case. This can be achieved by detecting convex ranges, as the constraints of convex areas do not interfere with each other.

- Adding the convex hull of the segments as a redundant constraint that does

not depend on any

only_enforce_ifcan in some cases help the solver to find better bounds.only_enforce_if-constraints are often not very good for the linear relaxation, and having the convex hull as independent constraint can directly limit the solution space, without having to do any branching on the cases.

Let us use this code to solve an instance of the problem above.

We have two products that each require three components. The first product requires 3 of component 1, 5 of component 2, and 2 of component 3. The second product requires 2 of component 1, 1 of component 2, and 3 of component 3. We can buy up to 1500 of each component for the price given in the figure below. We can produce up to 300 of each product and sell them for the price given in the figure below.

|

|

|---|---|

| Costs for buying components necessary for production. | Selling price for the products. |

We want to maximize the profit, i.e., the selling price minus the costs for buying the components. We can model this as follows:

requirements_1 = (3, 5, 2)

requirements_2 = (2, 1, 3)

from ortools.sat.python import cp_model

model = cp_model.CpModel()

buy_1 = model.new_int_var(0, 1_500, "buy_1")

buy_2 = model.new_int_var(0, 1_500, "buy_2")

buy_3 = model.new_int_var(0, 1_500, "buy_3")

produce_1 = model.new_int_var(0, 300, "produce_1")

produce_2 = model.new_int_var(0, 300, "produce_2")

model.add(produce_1 * requirements_1[0] + produce_2 * requirements_2[0] <= buy_1)

model.add(produce_1 * requirements_1[1] + produce_2 * requirements_2[1] <= buy_2)

model.add(produce_1 * requirements_1[2] + produce_2 * requirements_2[2] <= buy_3)

# You can find this code it ./utils!

from piecewise_functions import PiecewiseLinearFunction, PiecewiseLinearConstraint

# Define the functions for the costs

costs_1 = [(0, 0), (1000, 400), (1500, 1300)]

costs_2 = [(0, 0), (300, 300), (700, 500), (1200, 600), (1500, 1100)]

costs_3 = [(0, 0), (200, 400), (500, 700), (1000, 900), (1500, 1500)]

# PiecewiseLinearFunction is a pydantic model and can be serialized easily!

f_costs_1 = PiecewiseLinearFunction(

xs=[x for x, y in costs_1], ys=[y for x, y in costs_1]

)

f_costs_2 = PiecewiseLinearFunction(

xs=[x for x, y in costs_2], ys=[y for x, y in costs_2]

)

f_costs_3 = PiecewiseLinearFunction(

xs=[x for x, y in costs_3], ys=[y for x, y in costs_3]

)

# Define the functions for the gain

gain_1 = [(0, 0), (100, 800), (200, 1600), (300, 2_000)]

gain_2 = [(0, 0), (80, 1_000), (150, 1_300), (200, 1_400), (300, 1_500)]

f_gain_1 = PiecewiseLinearFunction(xs=[x for x, y in gain_1], ys=[y for x, y in gain_1])

f_gain_2 = PiecewiseLinearFunction(xs=[x for x, y in gain_2], ys=[y for x, y in gain_2])

# Create y>=f(x) constraints for the costs

x_costs_1 = PiecewiseLinearConstraint(model, buy_1, f_costs_1, upper_bound=False)

x_costs_2 = PiecewiseLinearConstraint(model, buy_2, f_costs_2, upper_bound=False)

x_costs_3 = PiecewiseLinearConstraint(model, buy_3, f_costs_3, upper_bound=False)

# Create y<=f(x) constraints for the gain

x_gain_1 = PiecewiseLinearConstraint(model, produce_1, f_gain_1, upper_bound=True)

x_gain_2 = PiecewiseLinearConstraint(model, produce_2, f_gain_2, upper_bound=True)

# Maximize the gain minus the costs

model.Maximize(x_gain_1.y + x_gain_2.y - (x_costs_1.y + x_costs_2.y + x_costs_3.y))

solver = cp_model.CpSolver()

solver.parameters.log_search_progress = True

status = solver.solve(model)

print(f"Buy {solver.value(buy_1)} of component 1")

print(f"Buy {solver.value(buy_2)} of component 2")

print(f"Buy {solver.value(buy_3)} of component 3")

print(f"Produce {solver.value(produce_1)} of product 1")

print(f"Produce {solver.value(produce_2)} of product 2")

print(f"Overall gain: {solver.objective_value}")This will give you the following output:

Buy 930 of component 1

Buy 1200 of component 2

Buy 870 of component 3

Produce 210 of product 1

Produce 150 of product 2

Overall gain: 1120.0

Unfortunately, these problems quickly get very complicated to model and solve. This is just a proof that, theoretically, you can model such problems in CP-SAT. Practically, you can lose a lot of time and sanity with this if you are not an expert.